Every year, when we commemorate Vietnam Veterans’ Day (18 August), it is an opportunity for us as a nation to acknowledge and reflect on the experiences of those who served in the Vietnam War and their homecoming.

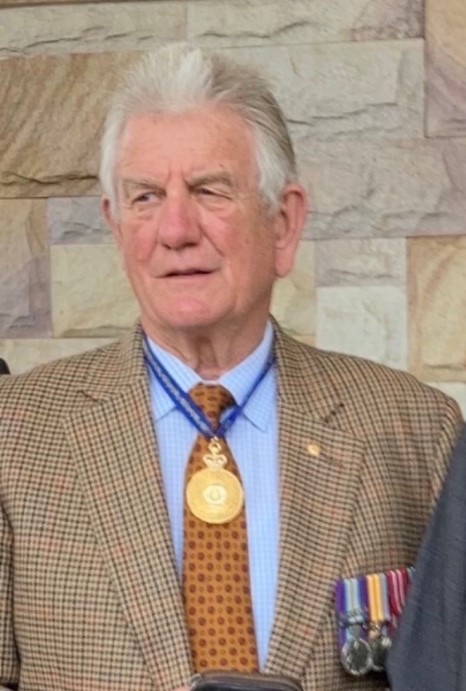

One such veteran is Christopher Madden AO, who was conscripted in 1970 after working as a teacher. He graduated from the Officer Training Unit as a 2nd Lieutenant. Chris served initially in PsyOps (Psychological Operations), and then with the 3rd Cavalry Regiment in the final stages of Australia’s involvement in the war.

‘Even my family didn’t really thank me when I returned,’ Chris recalls. ‘It was just something not spoken about. For the first 30 years of my working life afterwards, I don’t think anyone knew that I was a Vietnam veteran.’

In 1970 and 1971, increasing dissatisfaction with Australia's role in the Vietnam War led to major protests. Trade unionists, university students and academics, as well as others, began to strongly express their opposition to the war as it slowly wound down.

This broader societal backlash against a war not of their making left enduring psycho-emotional scars on Vietnam veterans.

Chris Madden takes particular exception to recent claims in the media that there is no evidence that returning Australian troops were ever spat on, that they were told not to wear their uniform in public, and faced protesters at airports.

‘Some historians place great emphasis on the fact that spitting on veterans was not reported and airport demonstrations did not happen,’ Chris says. ‘I’m sure they are correct. But it probably never occurred to them that traumatised young veterans don’t always act bravely or rationally to cruel, cowardly, and hurtful taunts from their fellow Australians. Perhaps dreadful injustices can happen silently: cruelties may not be reported. Perhaps, like domestic violence victims, young war veterans felt powerless and defenceless against bullies and cowards.’

These and other issues are explored in the ABC’s three-part series Our Vietnam War, produced last year for the 50th anniversary of the end of Australia’s involvement in the war, co-produced by DVA. The program concluded that there was a strong feeling among Vietnam veterans that Australia had not respected their service.

In part 3, former Sapper Robert Earle recalls a comment from a bar tender after ordering a beer in an RSL, while wearing full uniform and on walking sticks: You shouldn’t have been over there in the first place. ‘That hit me really hard,’ says Robert. ‘I wasn’t a war hero… it was just something thrust upon me.’

Chris Madden says that after returning from Vietnam and studying at university, groups of ‘brave students’ sitting around the university quadrangle booed, spat and hissed at him and another young veteran as they walked.

‘They weren’t trying to stop the war. They were cowardly attacking us in numbers,’ says Chris. ‘In a Sociology tutorial, when the tutor was told I was a Vietnam veteran he spat on me. No support came from the 14 or so students who saw him do this. I didn’t report this, as I was ‘off-balance’ after these experiences. I said nothing. I reported nothing. And I kept quiet about my war service for many years.’

It is good to know that societal views towards Vietnam veterans have changed. They now receive more respect and there is greater recognition and acknowledgement for their service and sacrifice. DVA would like to acknowledge the service and sacrifice of all Vietnam veterans and thank them for their service.

For an overview of Australia’s involvement in the war, please see our 50th anniversary commemorative publication, Australia and the Vietnam War, available on DVA’s Anzac Portal.

(Image: Christopher Madden AO)